One of my housemates is in a world mythology class. I was quite interested to hear this, since I love mythology, and I thought this might be an opportunity for me to increase the number of interests we have in common. I was rather shocked, therefore, to hear some of the on-line questions and discussions occurring in the class, which my housemate shared with me. According to my housemate, about 75 percent of the class are christian, and believe that mythos is “true,” as opposed to the “myths and stories” of other religions. Astonishingly, there’s even a christian creationist in the class who believes the story of Genesis is historical fact. Under the burden of that sort of conviction, my housemate is reluctant either to be rude, or to take on the task of educating the class.

One of my housemates is in a world mythology class. I was quite interested to hear this, since I love mythology, and I thought this might be an opportunity for me to increase the number of interests we have in common. I was rather shocked, therefore, to hear some of the on-line questions and discussions occurring in the class, which my housemate shared with me. According to my housemate, about 75 percent of the class are christian, and believe that mythos is “true,” as opposed to the “myths and stories” of other religions. Astonishingly, there’s even a christian creationist in the class who believes the story of Genesis is historical fact. Under the burden of that sort of conviction, my housemate is reluctant either to be rude, or to take on the task of educating the class.

I find it both astonishing and sad that people supposedly searching for higher education are so resistant to hearing new ideas, or even to finally grasping the concept of something so widely accepted and generally understood as, say, evolution. In some ways I suppose I lead a very sheltered life: I hang out with people who, like me, are college-educated, not particularly rigid intellectually, and not exceedingly religious. Perhaps most importantly, I prefer friends who’re comfortable enough with their beliefs and their sense of self that they’re willing to change their minds when they find new data, and who do not disdain those who believe differently than they.

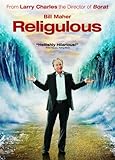

It’s that last one — having no need to mock those who believe differently than you do, who may have what you consider antiquated or ridiculously reactionary beliefs — which is perhaps both the most important to me, and the hardest to do. It’s also the reason I didn’t enjoy the movie “Religulous” and cannot recommend it despite a message I think is well worth promoting.

The sad thing is, this movie could have been a whole series of fascinating explorations of the world’s religions. It could have included data on how the modern interpretations of the religions — how they are actually lived today — endanger morality, or harm humanity, or inhibit the development of a better world. It could have showcased how people come to believe the things they do, and maybe even how they change their minds.

Unfortunately it did absolutely none of those things. Despite saying he wished to understand, Bill Maher spent all his time mocking others so he’d look smart. Instead of a thoughtful, rational exploration of how people come to their religious beliefs, he seemed to feel the need to produce what was effectively bad propaganda about his own beliefs.

I choose the word “propaganda” deliberately, although I wish it were inaccurate. However, many of the techniques used in the film were, as far as I know, classic tools in the creation of propaganda. For example, it was clear the film’s editors were cutting up the interviews to make people’s words appear more foolish — which simply meant I no longer trusted anything Maher was showing me. I also consider it a form of cheating, in filmed argumentation, to add in snide captions later, after the interviews — since the speaker can’t possibly reply to them. I was quite unimpressed with Maher’s use of stock photography as well, since he incessantly used film of people in various religious rites, spliced in with shots of terrorist bombings and atom bomb testing footage — as if they should all be conflated.

The interviews themselves were quite problematic for me, since Maher incessantly cut people off and wouldn’t allowing them to finish a thought. I was taught a good interviewer lets the interviewee talk — if possible, more than the interviewer themselves speak. Maher didn’t do that; we saw an awful lot of him asking others questions designed to make the interviewee feel stupid, and musing to himself later about how irrational they were and how he’d gotten over that nonsense, and interrupting his interviewees to ask in openly incredulous tones how they could believe things like that. Amusingly, when someone did the same to him — interrupting him and not letting him finish — he got annoyed, got up, and left! I couldn’t help thinking turn-about was fair play, really.

I ended up very uncomfortable with the level of hostility and mean-spirited mockery within the movie, to the extent that I would not care to be associated with it. I happen to believe we’d do well to dispense with all the various forms of thought (religion included) which teach us that those unlike us are stupid and wrong — the evil enemy who should be feared and murdered so as to restore good and balance to the world.

I don’t think we’ll reach the worthy goal of world friendship and peace, though, by brutally mocking those who believe differently than we do, and forcing them to see us as their enemy. Those techniques tend to backfire, causing people to feel either smugly self-righteous if they agree — or angry and emotionally besieged if they don’t, and to cling even more tenaciously to their beliefs. If Maher was trying to argue effectively for the death of religion with this movie, therefore, I’d unfortunately have to say he failed utterly.

To me, our culture has been incontrovertibly and dramatically changed. I don’t know how it quite happened. But, somehow — over the last 30 years is the number I’ve heard used the most — our culture changed. It became one where everything has a price tag. Where torture became acceptable. Where compromise is either mocked or given only lip service to. Where there is a growing tension. Where ‘Othering’ is routine.

One of the theories I’ve had is that the attempts at arbitration between the diverse aspects of Western culture over the past half-century, if not more, have only served to stave off, and in fact have intensified, feelings of irritation, anger, frustration, and anger between these ‘sides.’ Because of the lack of any satisfactory arbitration and resolution, the conflict between these differing views have made these groups isolationist. But now they can’t be isolationist because so many things are coming up that are forcing them to confront their beliefs. Some are accepting, but many are not.

That is why I feel that in the next few years, there will be some sort of mass disturbance which will spiral into mass violence. The isolated incidents — the LA riots, the Brooklyn Heights riots, etc. — will get more and more frequent and more and more violent. They will culminate in some sort of race/class warfare, and will very likely include an assassination attempt on President Obama, who is one of the polarizing figures in the current clash of beliefs. It will also likely involve assassination attempts on one or some of the most vocal right-wing pundits.

I don’t like the idea of violence, but Mike Malloy, a very, very left-wing pundit who is even more acerbic than Maher (I don’t agree with some of what he says, or the way he says some of it), but he does feel that this escalating violence will, ultimately, have a cleansing or cathartic effect. It’s not something to look forward to… but at least if we cannot prevent it, which I have doubts that we can, then something good will at least come of it. Just that after such a mass of violence, there’s a sense of catharsis. Like the quiet in the streets after a riot. It might be less ‘cleansing’ and just ‘resetting’ things, giving the survivors a chance to look at what happened and realize what went wrong. Not sure how much of that is actually the case. But I am pretty certain that the rhetoric will escalate into violence.

You know me, Greg: I’ll always suggest education and to attempt understanding and communication, before conflict. In the long run I do not doubt rationality and democracy and peace will continue to gain ground. I have to ask, too, why you’re letting their dogma determine whether or not you feel powerful. Isn’t that your own personal decision? ;)

The concept of mockery is one of the hallmarks of faux political/news shows like The Daily Show and The Colbert report…there is, of course, mixed feelings there as well. Because even though I find Jon Stewart very charismatic, and even quite intelligent when he’s making actual commentary and not just mocking, I do realize that the focus of his show is comedy, and not intelligent discourse. There has been conflict, as a matter of fact, in that he straddles that line between comedy and commentary, between humor and actual conversation.

The reason I bring up Jon Stewart, is that Maher does the exact same thing, in his show ‘Real Time.’ The irony there, though, is where Jon Stewart’s show is primarily humor mixed with commentary, ‘Real Time’ is supposedly commentary with some mockery thrown in. And yet, how is it that I find I take Jon more seriously? Is it purely Maher’s attitude?

Real Time brings on people of diverse views, invites them to talk, with Maher as moderator. Sometimes people more or less agree, and sometimes there is wild dissent. Sometimes Maher himself even makes good points. But even while he’s doing that, he still comes off as an asshole. The only reason one doesn’t notice it more often is that even as he’s doing this, people are *cheering* in the audience. People *like* this behavior from Maher. And that, I think, is one of the biggest problems. If there was no market, Maher would be doing something else.

So, while I agree with you in general in regards to Religulous serving no real purpose save for mockery, the bigger problem is that the supposed liberal, atheist population, that this is what many of them (and us) have come to. We feel powerless against people that cleave to stubborn dogma that makes no logical sense, so the only way we can fight it, or at least feel powerful again, is to ridicule it. The question we must ask ourselves now is: how do we get away from that?